Lichen

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Lecanoromycetes |

| Order: | Lecanorales |

| (Possibly in the Class Basidiomycota) | |

| (A lot are in the Suborder Lecanorineae). | |

| Family: | Parmeliaceae |

| Genus: | Parmelia |

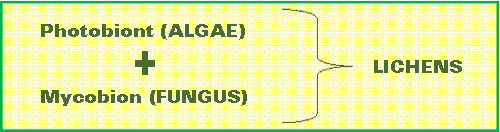

Lichen is often a complex organism comprising of a photosynthetic algae partner (the photobiont) and a fungus (the mycobiont) that grow in a symbiotic relationship.

The Photobiont could be an alga and/or cyanobacteria, both being equally capable of producing simple sugars by photosynthesis.

Fungi, however, are ‘heterotrophic’, needing an outside supply of food. The fungi set up the constitution of the lichen thallus, wherein they create the environment for an enduring, steady association with their photobionts (Algae), forming the foundation of the lichen symbiosis.

The body of the lichens is the “thallus” and it is distinct from those of the alga or fungus that grow separately. In lichens, the fungus encircles the algal cells, encompassing them with fungal tissues of a composite nature, a characteristic feature of the association of fungus and algae in lichens. Moreover, there is believable proof of the unfailing existence of non-photosynthetic bacteria in the all the lichens’ Thalli, though the role of those bacteria is yet mysterious.

Simply put, Lichens are atypical creatures. Unlike most other living beings, it is not a single organism, but a blend of two organisms that live closely together. Most comprise of fungal filaments.

It is normal to find alga and the fungus, the two constituents of lichen living in nature alone without respective partners. Yet, many lichens contain a fungus that cannot survive by itself and depends on its algal partner for its survival. However, in each case, the form of the fungus in the lichen is rather different from its morphology as a singly growing entity.

There is enough support for considering the lichen symbiosis as a mutualism, wherein both the partners gain from the relationship. It is obvious that fungi get their carbon-source by way of simple sugars, but apparently, the photobionts (algae) also get favorable conditions for survival. Perhaps, the photobiont also gains from better access to mineral nutrients that are present due to fungal digestion external to their cells.

History on Earth

Geological proof, indicate that fossils existed 400 million years ago, though there are indications of the existence of their earlier forms 600 million years ago, meaning they were certainly among the earliest forms of life on earth. From, the number of algal and fungal species available on record, one can safely assume that the symbiosis between different species should have taken place a number of times. Many people think that a few or all the Ediacaran biota could be lichen. On getting an appropriate and long lasting substrate, and left on its own, lichen can usually survive for many centuries. A certain arctic sample of crustose lichen, Rhisocarpon geographicum, was nearly 9000 years old!

Note: Ediacaran biota

These organisms probably embody the earliest forms of a multi-cellular organism and date back in time to the Avalon Explosion almost 575 million years back.

Types

Lichens grow in many forms; the simplest are the crusts of slackly mixed algae and fungal hyphae, while the rest are very complex, having shrubby or leafy forms like tiny trees. Some attach themselves to the surface by means of their special structure.

- Crustose lichens, true to their name, are encrusting forms that grow inclusively into their habitat. You cannot remove them from the attached surface unless you crush them out.

- Foliose lichens have leafy lobes, fanning horizontally on the surface. You would require a knife to pierce out the root threads.

- Fruticose lichens appear in a shrubby form, having a number of branches. You can easily use your hand to detach them from their surface.

- Leprose lichens comprise of a powdery mass having little or no structured configuration

- Squamulose are quite like crustose, but with raised edges that you may see folded and lobe-like.

Habitats

Perhaps they are the only plant form existing in some such areas including not so harsh climates, living in almost any solid surface that may vary from rocks on seashores to trees, walls and concrete. Only some unattached ones can blow freely. You can surely consider this as a main source of food for animals. You can also find them in some of the most inhospitable environments on the planet, including the hot deserts, the arctic tundra, rocky coasts and toxic slag heaps. You can also find them abundantly in the form of epiphytes (plants that grow on other plants non-parasitic) on the branches or leaves of the trees in the temperate woodlands or the rain forests, on exposed rock surfaces including gravestones.

Uses

Lichens have served many uses since long. Before the late advent of the present dyes, these formed a vital source for dying of clothing. Different lichens delivered varying colors and these combined to get a large range of colors.

The chemistry of lichens is very exciting, and they produce a variety of acids, many of which one can derive from lichens. The litmus dye, extensively used for identifying an alkali or acid is a derivation from lichens. Some varieties possess antibiotic properties. Many people use certain acids derived from lichens for making drugs that are more helpful than penicillin.

It is also interesting to point out that, in ancient Egypt they used lichens for packing Egyptian mummies.

Reproduction

The different processes of reproduction of lichens are as under:

Small parts that break off and grow at some other place

Or by production of spores by the fungal partner. A white powdery mass can cover their surface. These comprise the minute body parts of lichen that they shed to produce new lichens. Soredium is the name given to the individual body parts, containing the fungus along with the algal partner.

Generally, fungal spores grow in the apothecia (cuplike Ascocarp or mature fruiting body in many lichen fungi) or in perithecia (A small flask-shaped fruiting body in fungi that contains the ascospores) on the surface of the lichen. The fungal partner delivers the spores and these have no algal cells.

Growth

Except for fruticose, the growth of all lichens is very slow, from just half to five mm per annum, measured in terms of the growth of their circles. Fruticose lichens grow up vertically and rapidly, up to two cm per annum. The rate of growth varies with the species and the surrounding environment. The smaller varieties may have a growth of just one mm per annum. The larger varieties could grow up to one cm per annum.

Having discovered a fondness for insects while pursuing her degree in Biology, Randi Jones was quite bugged to know that people usually dismissed these little creatures as “creepy-crawlies”.